This BAFTA- and Oscar-winner walks us through his process.

When I first spoke with Ben Wilkins, he was freshly back from the Oscar-nominee luncheon in Hollywood and about to head to his native England to attend the BAFTAs. Wilkins was nominated by both academies for his post sound work on Sony Picture Classics’ Whiplash, the Damien Chazelle-directed film about an aspiring jazz drummer and his brutal instructor.

Wilkins (@tonkasound) didn’t return to LA empty handed — he, along with fellow sound re-recording mixer/co-supervising sound editor Craig Mann, and production sound mixer Thomas Curley, brought home the BAFTA in the Sound category.

As their titles imply, Wilkins and Mann, both based out of Technicolor Sound on the Paramount lot in Hollywood, had dual roles on Whiplash. This is actually a growing trend in Hollywood — one person, multiple disciplines. “It used to be that you needed a very specific set of skills; it was very specialized,” says Wilkins. “But now it’s more democratic, thanks to the democratization of the tools.”

I asked Wilkins if he was enjoying this trend or if he’d prefer to focus on just one aspect of the audio post. It seems Wilkins might be a control freak, and I mean that in the best possible way. “If it was up to me, I would want to record the sound on set as well, and I have done that before. To be able to see a project through — from inception all the way through post production to the theater — is a huge privilege, but one that doesn’t happen very often.”

While this elusive process of taking it from to start to finish didn’t happen on Whiplash, Wilkins and Mann’s workflow on the film didn’t miss a beat. In fact, Wilkins likens his work as a mixer and editor to that of a sculptor. “When I’m editing, it’s like I am putting matchsticks together to build a giant block of wood in the shape of whatever sculpture I am doing. Then when I switch to mix mode, it’s like I’m taking a blade or chisel and removing extraneous sound that doesn’t advance the story and doesn’t help the audience emote.”

Ok, now let’s dig into Whiplash’s audio post workflow.

How did you get involved with Whiplash?

Craig and I had worked for the production company, Jason Blum’s Blumhouse Productions, before. They have an existing relationship with Technicolor Sound and we were able to accommodate their schedule and their budget.

How did you work with the director? How did you guys communicate?

It was a good relationship. We had a very long initial meeting with him in the editing room. We watched the film and talked about how we were going to handle things. As I mentioned, the schedule was very tight, so we quickly developed a sense of Damien’s audio shorthand and what he was feeling and what he wanted to hear.

He was extremely decisive in how he wanted things to sound. He had a very definite idea in his mind before he heard anything. He knew what he wanted – the character in film is essentially based on him, so he knew what specific rooms and situations should sound like.

What’s an example of a direction that he gave you?

A big one involved the practice rooms, or the band rooms, which were mostly subterranean. We were based in New York and they were underground and sort of womb-like, and there wasn’t a lot of outside sound — that was something he wanted.

In an earlier version of the film, we had a lot of New York sounds: sirens, cars, horns and the usual sort of noise. In general, it sounds very loud and very pervasive, even in interiors. Damien was very sensitive to those sounds, and we ended up removing nearly all the background when we were inside the practice rooms. He was right. To hear sirens of a police car go by while someone is sitting, waiting for a teacher to show up for a drum lesson isn’t necessarily advancing the story.

So complete focus on the characters? No outside intrusions?

Yes, almost like a vault or a temple or a church. Somewhere very peaceful, where the musical instruments and the people inside the rooms were making all the sound.

L-R: Craig Mann and Ben Wilkins on the mix stage at Technicolor Sound.

How did you and Craig split the work?

He handled editorial for dialogue and ADR. Actually, we both worked on the dialogue and ADR, and then I handled the Foley, the background, all the sound effects and all the sound design. That was how we divided up the editing work. We also made fine adjustments to the music whilst mixing.

Can you walk me through your process?

We got a cut that was pretty close from the picture editor Tom Cross, and we had about 20 or 22 sound rolls, which we loaded in. We assembled the dialogue from dailies using SynchroArts Titan software and assembled that into Avid Pro Tools sessions. Same with the Foley and ADR; basically everything was recorded into Pro Tools.

So we recorded the ADR and Foley. Then I recorded some background, specifically for this show — a lot of the background involved musical instruments being played off screen, or musicians tuning their instruments and bands warming up off camera. There is a musicians’ union band practice room quite close to the studio, audible from the street.

We then took that library of sounds and started editing to picture. We prepped all the tracks to picture and after about five weeks, we took it down to the mixing stage here at Technicolor. Using the Euphonix S5 Fusion console, we then mixed all the material we prepared, along with the new music and the old music, into the final mix.

What do you think stood out about this film in terms of its sound? What made BAFTA and the Academy take notice?

No matter how good the sound is, I think all of the films nominated this year have some emotional component that spoke to the viewer and helped them really key in to certain sounds that resonate within the soundtracks of these films.

When you’ve got a film that’s about people playing instruments, and the relationship between those people who play, their actions become incredibly key to their story, and in this case it was really enhanced by the emotional content of the soundtrack.

How much of the actor’s drumming performance was post-sync?

That’s a tricky question to answer, but I’d say about 20% of the drumming in the soundtrack was recorded on the set. About 60% of the drumming was pre-recorded and played along to, and then about another 20% of the drumming was recorded afterwards.

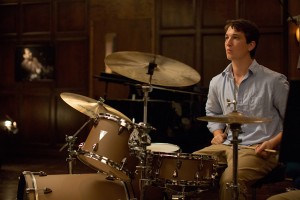

Did the lead actor Miles Teller actually play the drums on camera?

Miles took a lot of intensive training lessons before the filming started, and he was at a pretty high standard. The thing about the film is that these players are exceptional. I’ve used the analogy of Natalie Portman’s ballerina in Black Swan. It’s a similar situation here. These people have been practicing and honing their skills for years, so unless you can find a drummer who can act or a dancer who can act, you’re only ever going to approximate or get some sort of portion of the truly excellent performance.

The person who played the drums we hear in the film, did they perform to picture?

Yes and no. That professional drummer played ahead of time. In other words, there were scenes where there was pre-recorded music that was played back on set, and he played those scenes.

Afterwards, we called it Drum ADR — there was automated drum replacement recordings where we went back and he did play to picture. It was very challenging for him. It was not something he had done before.

Were reverbs used to put the post-performance drum parts into the scene?

Yes. Very special reverbs were used. We went on set and recorded impulse responses. In other words, we made computer models of the reverbs — the real way the room sounded on set. Both of the mixers, myself and Craig, were able to be perfectly in sync, audio-wise, in terms of what reverbs we were using for dialogue and ADR, music, Foley and effects.

All Whiplash Photos Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

Thought Gallery Channel:

Creative Master Series